Further Analysis of the Honda Civic Head Unit Firmware and SD Card (...and the Brick It Became... oops)

Happy New Year, Honda fans! I rang in the New Year by spending more time going over the Honda Civic head unit. It was very exciting to learn more about this head unit. I’m excited to share my findings below!

Rebuilding NK.bin for Analysis

The next thing I wanted to try was using some of the original Windows CE development tools against the NK.bin I extracted from the SD card. The main tool I had in mind was dumprom.exe, which is designed to take an NK.bin and break it back out into its individual components, mainly EXEs and DLLs.

Unfortunately, dumprom.exe wouldn’t run against the NK.bin I initially extracted using binwalk. After digging into this a bit more, I realized I needed to take a different approach. Instead of working with NK.bin directly, I wrote a small Python script that takes all of the individual .bin chunks that binwalk extracted and merges them back together into a single, flat memory image. The result of that process is a file I called mem_flat.bin.

WinCE NK.bin itself is a record-based format, not a traditional filesystem. Because of that, executable images can be split across multiple records, and simply scanning the raw file for PE\0\0 signatures can miss real modules entirely. Binwalk had already given me a directory full of 8E……..bin chunks under extractions/NK.bin.extracted/0/, each mapped to a specific address. By stitching those chunks back together into a contiguous RAM image, I could then scan it properly for PE headers and strings.

From inside the folder that contains the 8E*.bin files (extractions/NK.bin.extracted/0/), here is the Python script I used to create the flattened memory image.

python3 - <<'PY'

import os, re, struct

files = []

for fn in os.listdir("."):

m = re.fullmatch(r"([0-9A-Fa-f]{8})\.bin", fn)

if m:

addr = int(m.group(1), 16)

files.append((addr, fn))

files.sort()

print("chunks:", len(files))

if not files:

raise SystemExit("No chunks found.")

base = files[0][0]

end = max(a + os.path.getsize(fn) for a, fn in files)

size = end - base

print("base:", hex(base), "end:", hex(end), "size:", size)

mem = bytearray(b"\x00" * size)

for addr, fn in files:

off = addr - base

b = open(fn, "rb").read()

mem[off:off+len(b)] = b

open("mem_flat.bin", "wb").write(mem)

print("wrote mem_flat.bin")

# scan for real PE headers in the flattened memory

hits = 0

i = 0

while True:

j = mem.find(b"MZ", i)

if j == -1:

break

if j + 0x40 < len(mem):

e = struct.unpack_from("<I", mem, j + 0x3C)[0]

pe = j + e

if pe + 4 < len(mem) and mem[pe:pe+4] == b"PE\x00\x00":

print("PE at", hex(base + j), "file offset", j)

hits += 1

i = j + 2

print("PE hits:", hits)

Further Explanation on Why dumprom.exe Failed on the Original NK.bin

One thing worth explicitly calling out here is why dumprom.exe failed when pointed directly at the NK.bin extracted from the SD card, but worked once I rebuilt a flattened memory image. NK.bin is not a traditional PE container or filesystem; it is a record‑based format designed to be mapped into memory by the bootloader. Because of that, executable images can be split across multiple records at different addresses. dumprom.exe expects something much closer to an in‑memory view of NK.bin, not the raw record format, which explains why it initially failed and then worked once everything was stitched back together.

Results from dumprom.exe and eimgsfs.exe

After doing that, I ran mem_flat.bin through both dumprom.exe and eimgsfs.exe and it worked! You can see the results of each in the text files below:

The findings from that are very valuable. We can see a few .exe files and a ton of .dll files, as well as some others. See the link at the end of this post for more information on the files found.

Bitmap Assets on the SD Card

There are several bitmap files on the SD card. They all seem to be related to the pre-OS stuff like updater and thermal warnings. Interestingly, the update-related ones each have two versions: one that lists USB as the update method, and one that lists CD as the update method. For example, “Copying… Please do not turn off the vehicle or disconnect the USB device.” vs “Copying… Please do not turn off the vehicle or eject the disc.” This means both USB and CD drive can be used for updates.

I was searching the contents of the card to try and find out how the text is displayed. My initial theory is that it utilized bitmaps or other images representing each character. I was unable to find anything like this on the SD card; however, during my search, I did discover a very interesting image.

This code:

python3 - <<'PY'

import os, struct

IMG="civic_dump_raw.img"

OUT="all_bmps_from_img"

os.makedirs(OUT, exist_ok=True)

with open(IMG,"rb") as f:

data = f.read()

n=len(data)

count=0

i=0

# size filters

# fonts are often tens or hundreds of KB, not tiny icons

MIN_SZ=20_000

MAX_SZ=2_500_000

while True:

j = data.find(b"BM", i)

if j == -1:

break

if j+6 <= n:

sz = struct.unpack_from("<I", data, j+2)[0]

if MIN_SZ <= sz <= MAX_SZ and j+sz <= n:

# quick validity check: DIB header size usually 40, 108, 124

dib = struct.unpack_from("<I", data, j+14)[0] if j+18 <= n else 0

if dib in (40,108,124):

fn = f"bmp_{count:05d}_{j:08X}_{sz}.bmp"

with open(os.path.join(OUT, fn),"wb") as o:

o.write(data[j:j+sz])

count += 1

i = j + 2

print("Extracted BMPs:", count)

PY

extracted a single image that I still can’t wrap my head around. As you can see below, it is almost the same resolution as the head unit, and contains text relating to a Honda dealer called “Germain Honda”. This is the dealer where I suspect the car was purchased from when new. This image was likely either displayed after first purchase, or I think it may be displayed after the vehicle is serviced by a dealer.

Dealer Splash Image as a Provisioning Artifact

The presence of a full‑resolution, dealer‑branded splash image embedded directly in the SD card image is especially interesting. Given its resolution and content, this does not appear to be a generic UI asset. While I can’t find any public documentation on this, the most reasonable explanation based on what I’m seeing is that this image was written to the card during dealer provisioning, initial delivery, or a service event, and then displayed once during boot. I haven’t been able to find any references to this behavior online, but the artifact itself is very real.

Testing the Role of NK.bin on the SD Card

After further dissection of the SD card contents, I wanted to know if we could swap an NK.bin file onto the SD card and see if it might boot that or behave differently. I extracted the NK.bin from the SWUpdate.mef (from the CR-V CarPlay update) file, and then swapped that into the SD card image. The head unit booted fine and no behavior changed.

I also purposely corrupted the NK.bin gzipped portion altogether to see how it might behave, and it still booted fine. So the SD card is likely just asset/map data (images etc.), config, and some app data. More than likely the actual runtime stack is stored internally on the radio itself. Bummer!

This, along with the general contents of NK.bin, leads me to believe that the SD card is in fact not the actual OS the radio runs, but rather all image assets, map data (if equipped), config, and some files relating to the radio boot and update process. This makes our goal of reverse engineering a little bit harder. However, this does mean that one can freely change the image assets on the card if they want to adjust the look of the radio, but this would be very involved.

SD Card Layout and Architecture

This means the architecture of the SD card contents is essentially as follows:

Layout:

Sector 0 : MBR (mostly empty)

Sectors 1–31 : padding / reserved

Sectors 32–557055 : FAT16 partition (empty by design)

Sectors 557056+ : Raw Honda data region

├─ NK.bin.gz

├─ UI resource packs

├─ image blobs

├─ config tables

└─ crypto / update logic

This makes me believe that the actual OS files (text, exe that runs the radio, etc.) all live on the internal flash. This is a bit annoying, as this makes the process of changing those a bit harder. This is further confirmed by the contents of the dumped log files from the hidden menu within the radio. Inside of the hidden factory diagnostics menu, there is a way to dump and output log files from the radio. Inside of these logs, there are references to executables like HMIMANAGER.EXE, AV.EXE, PLAYER.EXE, MISC.EXE, TUNER.EXE, DIAG.EXE, MIRRORLINK.EXE and COMMUNICATION.EXE. None of these are present on the SD card itself, which means they likely live in internal flash. You can take a closer look at the dumped log output files at the end of this post.

Why the FAT16 Partition Is Empty

One thing that stood out to me early on was that the FAT16 partition on the SD card is essentially empty by design, while all of the interesting data lives in the raw region after it. Based on how the card is laid out and how the radio behaves, this FAT partition appears to exist mainly for compatibility or tooling reasons rather than actual runtime use. All meaningful assets, configuration, and update‑related data appear to live outside of it in Honda’s own layout.

Evidence of Internal Flash Storage

Another interesting find within the log files is mention of cold boot logic. I suspected the radio was already doing something like this but these files confirm it. Essentially, there is a snapshot of the last known good boot arguments, configuration, etc. stored as a compressed file likely on flash. Then, when the radio cold boots, it utilizes this to ensure it boots quickly. See the beginning of the SER_MSG.LOG file here:

Cold Boot and Snapshot Behavior

Startup Loader : H14M DA US 3.28 **/

/********/

CE 700

[0x0][0xFFFFFFFF][0x0][0xFFFFFFFF]

<<< Cold Boot >>>

SnapShotBoot

cur backup

17FFFFF0 : 02080181 58001228 00011228 2320687D ....(..X(...}h #

backup sum 0x00011228, calced 0x4F37853E -> NG

Attempting a Modified Update (and Bricking the Unit)

I then decided to try one more time to modify the CR-V Carplay update file to see if I could just get it to do something, anything! At this point I have been largely unable to have anything of value to show, so I was eager to get something to work. As far as I can tell, these updates are cryptographically signed, so the chance of it working is essentially zero, but I was riding on the power of dreams here! Ha!

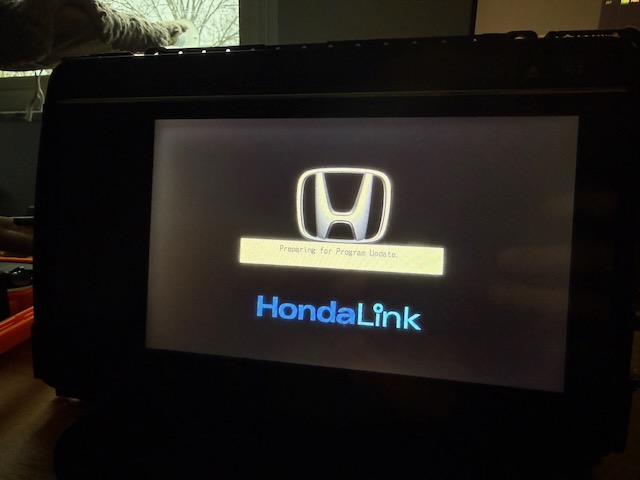

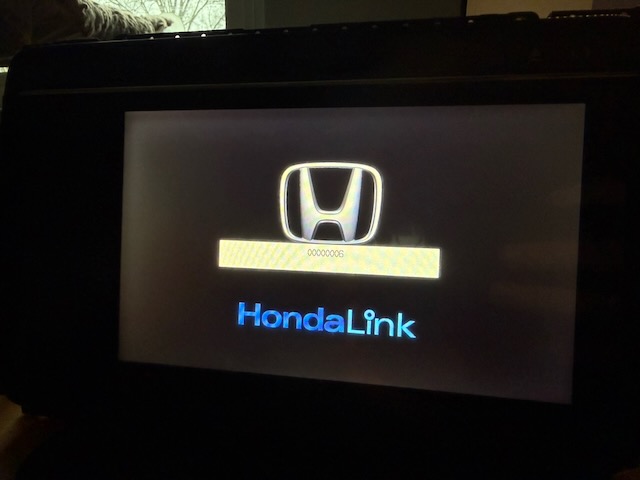

I forced the update via the hidden menu in the radio screen, and as expected the radio rebooted. It showed “Preparing for program update…” as it has for me before when messing with this process, then showed “00000006”. Oh well, so it didn’t work. I power cycled the radio after removing the USB and, oops! The same message is back. I power cycled a few more times, and it’s still there! I even let it sit for hours unplugged. No dice. I then tried the handful of different backup SD cards I made in case I corrupted the main one, no luck either. So at this point, I think I have soft-bricked the head unit. Major fail! I guess this is a good way to convince my wife to let me buy a hot air rework station and an Xgecu T48, ha! More than likely what needs to happen is the onboard flash and possibly EEPROM both need to come off and be flashed to tell the unit to not expect an update. The unit appears to be stuck in a state where it is expecting an update on boot and does not proceed until it has one.

The Likely Cause of the Bricked State

Based on the behavior I’m seeing, it seems very likely that the unit is stuck in a state where a persistent flag has been set telling the bootloader to expect a program update. When the update process fails or cannot find valid media, the unit never exits that state and simply hangs on boot. I don’t yet have direct confirmation of where this flag lives, but given everything else observed so far, internal flash and possibly EEPROM are the most likely candidates. This is something I plan to investigate further.

I will fix this at some point, but for now, it is back to researching the files themselves while I decide on the best path forward.

Educational Research Notice

The following materials are provided solely for the purpose of technical analysis, reverse-engineering research, and interoperability study.

The data was obtained from hardware lawfully owned by the author. No warranties are made, and the materials are provided as-is for examination and research only.

These materials are not intended to enable infringement, commercial use, or unauthorized distribution of proprietary software. If you do not have the legal right to access similar data, do not download or use these files.